-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 221

Tutorial: Create Your First Kata

Okay, so you might have completed many (all?) of the published katas on Codewars. But... that's only half of the battle.

There is an obvious elephant in the room: Where do the katas come from? Obviously they didn't come out of nowhere like inside a stone or from a big bang, so clearly someone, or something, must have created the kata.

Being intrigued, you looked at the Kata Creator again. Maybe you should create a kata.

Creating a kata is a totally different kind of task from solving a kata. You might be able to solve a purple kata in under an hour, and still get flummoxed by the process of making a new kata. Being a good player doesn't always make you a good level maker, after all.

While a kata with minor problems can be easily fixed, a kata with fundamental issues will get stuck in the beta process forever. You don't want that.

At the time of writing, there are already over 3500 published katas, and almost 3000 beta katas. It's a vast red ocean out there - if you're still sticking to ideas like Fizzbuzz, Fibonacci numbers or Caesar/ROT cipher, it's pretty much 99.999999...% i.e 100% that someone will have done this before you.

This is bad because creating a kata about them again constitutes a duplicate kata, and we certainly don't want 100 Fizzbuzz katas out in the wild. When a duplicate is found it will be "retired", which basically means it gets taken out of the kata catalog.

As we all know, before you even engage your enemies, you need to send scouts forward.

For example, while Peano and Church numbers are definitely not easy, as the search results clearly shows, they've been done many times already.

In a way, knowing the katas in the wild is very similar to knowing your enemies: you get to see how others write the same kata, other people's (sometimes) brilliant solution in these katas.

Then, maybe you can decide whether to retreat, or make a harder version of the kata as return if you feel the existing one is too lackluster/easy.

If you find yourself worrying about hitting duplicates all the time, then try to push yourself to think out-of-the-box. Don't worry, coming up with good ideas are hard! But if you can make sure your ideas are always novel and/or original, then you can be almost certain nobody will have taken the flag before you.

It also has a side benefit of making people think that you're clever, which will be reflected on the satisfaction rating.

Naturally, when you've already solved 10 fibonacci katas, solving another one will make you very nauseous, making you naturally allergic to duplicates ;-)

While the minimum honor for creating a kata is merely 75 honor, if you try to create a kata with just 75 honor, it'll most likely inadvertently be bad.

Why? With just 75 honor, you haven't even get a grasp of what katas are actually like.

Anyone can reach 75 honor in a very short time, from a few hours to a day or two. This is, obviously, far from enough. Thus, you need to train more.

Solving more kata with more experiences can help one very significantly on these aspects:

- Getting more experienced will help you understand how hard your kata is, so that you can tune your kata to your desire easily.

- As you train more, you tend to know what the most efficient solution for a kata is. This is crucial to performance and golf katas: you don't want to make a performance kata when you can only write sub-par solutions! You'll get pwned hard by veterans ;-)

- Actually encountering kata issues and looking at comment sections will let you understand the common issues people will raise. Learn from the history, and don't make the same mistake again!

- Looking at solutions (and more importantly, solution comment sections) will give you insight to what'd be good practice

- It also allows you to see how others write their tests. Writing good tests are hard, especially if your kata is also hard.

Before you start actually writing the requirements and the tests, you need to ask yourself:

- Which kind of kata does this kata belongs to?

- What do I want to assess the users on in this kata?

Getting these questions answered yourself will help you pinpointing the kind of solution and tests you need to write, and the overall difficulty of the kata.

Katas are usually divided into several categories:

Fundamental katas are easy problems intended to teach people basic aspects of programming and concepts. They consist of pretty much all the white katas, and some 6kyu katas.

Since they're going to be faced by lots of inexperienced users on CodeWars, everything should be clear, concise and complete, and there should also be clear feedback. You want to teach them and help them learn, not suffocating them with harsh, unforgiving material.

Good qualities in fundamental katas include:

- A well-written and concise description explaining the concept

- Links to necessary resources

- Good example tests

- Responsive test feedbacks and full coverage of edge cases

These things will immensely help people not familiar with the subject in question to grasp the concept.

Bugfix katas are not like your regular katas: instead of coding a solution up from scratch, a piece of code is already provided; however, it is not passing some of the requirements because of a reason, and you need to modify the code (hence bugfix) to make it work.

Good qualities in bugfix katas include:

- Already comprehensive example tests to give users a basis for fixing the bug

- Initial code that complies to the code convention for the language

- Featuring a central, key concept

- Especially better if such concept is a very common but subtle pitfall to even experienced programmers

However, because some people thought that bugfix kata is subjected to lower requirements than normal katas, there had been lots of bad bugfix katas. These things are what you shouldn't do in bugfix katas:

- A "pseudo-code" program written in unknown, self-invented syntax that will not even compile at all

- Highly obfuscated or ugly programs

Basically, if a bugfix kata features code that is so smelly rewriting it from scratch would be more pleasant and faster, it stops being a bugfix kata and becomes a regular kata.

Algorithm katas, as it's named, test the user on writing a good algorithm for the task in question. How good an algorithm needs to be, or how hard it is to come up with the algorihm, varies from problem to problem. They might also have varying degrees of performance requirements.

Good qualities in algorithm katas include:

- A clear description of the problem

- Thorough tests, excellent coverage and complete testing of edge cases

- If performance is required, specify the input range and number of tests

Puzzle katas are not your regular katas. They are more like actual puzzles and games - the coding part might be very easy even for beginners, but it is not apparent what the steps are. Puzzle katas also generally includes recreational programming puzzles - code golf, source restrictions, environment investigation, cop and robbers, etc.

Good qualities in puzzle katas include:

- Actually being a puzzle (i.e don't give big, big hints right away)

- Well-designed and coherent puzzles

- Subtle but adequately planted hints

- Puzzle elements that is not finicky - if a user gets the puzzle, he should not need to do lots of fumbling and trial-and-error to get them to work

Needless to say, it requires lots of ingenuity to pull of a puzzle kata. It's not for the faint of heart - it's very easy to make a puzzle kata that is a "guess the author's intent" kata, or a "trivial puzzle" kata. They're not very interesting.

Challenges katas are very, very tough problems intended to give a challenge to even the veterans, which are, by their nature, difficult to be challenged (otherwise they wouldn't be "veterans"), so one has to go really far to impress them.

Naturally, a challenge kata should not just require people to code brainlessly and pass in a few minutes. It should not just be tough to newbies - it should be tough even to experts.

Good qualities in challenge katas include:

- A good description to present the problem

- Require lots of experience and/or background research to even figure out the possible approaches

- Require careful planning to formulate a line of attack

- Even with that, might still require hard work and clever approaches to succeed

Things that you should avoid in challenge katas:

- Total lack of mercy. If you require everyone to write the fastest micro-optimized solution, then only the fastest micro-optimized solution will pass. There should at least be some leeway so people don't have to, again, juggle 10 things at once and get annoyed

- Difficulty by obscurity. Inflating challenges with "guessing the intent" is never a good practice. See also: the point in "Puzzle kata" above

Remember, after all the best challenging puzzles are not about puzzles, they're about experiences. When you can craft puzzles that makes people experience and remember the process of figuring it out, you'll have truly become the master. This is what people mean when they say "when I finally solved this I felt very satisfying".

Projects are kata that are about implementing an actual, working product according to specifications. They almost always require to juggle several things at once. The product can range from anything small to big - a custom helper class, to a full-blown interpreter/solver or engine.

Good qualities of project katas include:

- A good intention/introduction opening to tell people why such project would be useful

- Well-written, well-organized and clear specifications

- Thorough tests that are broken into pieces (i.e unit tests) so that people can test one aspect/component at a time

A good project kata can teach people how to build up a full, working project that solves a general problem from scratch, instead of just a tiny program that solves a very specific and narrow task.

Have you encountered that feeling when you're met with a requirement you can't understand because it's poorly and inadequately written, and you still have to fulfill the requirement?

Don't let yourself be the guy who wrote this. If you ended up conjuring such hot garbage, everyone will just keep themselves away from 10 miles away and nobody will finish your kata.

A description should:

- Provide a sufficient and complete description and requirements of the task

- If it provides some back-story, it shouldn't be so long that it overwhelms the kata itself

- If complex steps are involved, give an actual step-by-step example

- Lists all the edge cases, edge conditions and required error handling if they're required

- Be structured well so that people can read from top to bottom as they implement the requirement sequentially

- Make proper use of Markdown to convert walls of text to more readable formatting, e.g paragraphs, lists, code blocks

- Highlight really important things (e.g

round to 2 decimal places) in emphasis, e.g in bold

An extensive use of Markdown will significant help the readability of the descriptions. Codewars uses an expanded version of GF Markdown so make sure to check the documentation.

Fortunately, if your kata description is not very good, people will be eager to point this out in the comments, so you have more than enough chances to fix them.

Additionally, if you're writing performance/algorithm katas, you should provide the data range. It helps people to gauge how good their solution needs to be.

Incidentally, "guess your intent", or guessing in general, is seldom a good puzzle. It requires very delicate skills and experience to pull off well. If you are going to attempt this, please make sure to seek out other kata and learn from what works and what doesn't.

If you ask people to do 10 katas about 10 different things, that's okay.

But if you ask people to do 1 kata which needs to do 10 different things depending on some arbitrary conditions, nobody will ever like the kata. Juggling 10 object at once is not fun.

This often happens for unbalanced katas - while they're asking for doing one thing, because of how the kata is written the actual difficulty lies on something completely unrelated to the proposed intent of the kata itself, e.g doing a task with a very unnatural and hard to work with input format.

If you find that your kata is too long, mostly from these symptoms:

- your kata has a very long description

- a typical solution is very long and yet none of them is hard, the only difficulty is from the tediousness

- your kata requires doing many things together

, you might want to break up your kata in separate parts if appropriate.

Quoting power user @JohanWiltink's comment on one of the beta katas:

And, again, you're doing multiple unrelated things in one kata. Totally unrelated, neither of them trivial this time. What is the intent, what is the pointe of this kata?

(Please note: a pointe is not a point. I'm not implying this kata is pointless. If anything, it seems overpointed - in width, not in depth.)

While the old katas are usually lazy and only has a few tests, nowadays if you try to pull off the same trick you'll instantly get yelled at with all the Needs random tests!!!!!11!1 and your satisfaction rating plummets to 0%.

For normal katas, a good set of tests should cover all these aspects:

- Test basic functionality

- Has full coverage (if that's impossible, at least have decent coverage)

- Covers edge cases thoroughly

- Randomized so pattern-matching against the tests are impossible

- Stress/performance/code characteristic tests if needed

The first three should be put into fixed tests. The fourth item should be put into random tests. The last item should be put in isolation, though it is optional.

Sample tests are not required in general, but you should provide sample test cases. These are the starter test cases that users will see when they load the kata.

You can include a few tests to get someone started, though of course if you're lazy you can just copy static test cases from the actual tests over. Just don't copy your reference solution there as well.

Unless you intend the users to write tests themselves, or such is not applicable for your kata (Example: Diffuse the bombs), it's usually considered a good practice to provide example test cases to the users.

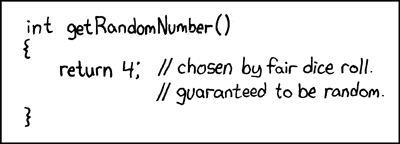

(Source: xkcd)

Random test cases are test cases that cannot be predicted. Most kata have them (except for the really old ones) and they are usually in addition to some static tests. Using both static and random test cases with make it both easy for warriors to see what they are supposed to do, as well as make it impossible to write a solution that just pattern match the inputs (i.e return hard-coded outputs depending on a fixed set of inputs).

Remember: just like in real life, if we failed a test, we want to know:

- what input failed

- expected and actual result

So unless revealing the expected result would spoil the kata, you should not hide them. Consult the testing framework and pick the best method for your tests. (Protip: except is almost always never it.)

...Yes, who said writing tests are easy? Learning how to use the testing framework properly is part of learning how to code!